In València’s Ethnographical Museum there’s a temporary exhibition on at the moment called Arqueología de la memoria. Las fosas de Paterna (An Archaeology of Memory: the Graves of Paterna). Paterna is a municipality about 10 kilometres from Valencia and it has the bitter distinction of being the site of the second largest number of Republican prisoner executions during the Franco regime. The executions started just five days after the end of the Spanish Civil War in April 1939 and they continued until 1956.

Officially 2,238 Republican sympathisers were executed, though there are likely to have been more. Across Spain there are at least 2,500 mass graves holding the bodies of about 130,000 victims of the Civil War and Franco’s subsequent dictatorship. There may be twice as many as that, some of which will have been lost forever, razed by the heavy machinery that moved into cemeteries across Spain in 1975 after Franco’s death to destroy the evidence of his brutal repression.

The Paterna cemetery was spared, which is why every Monday forensic archaeologists work on one of the 135 mass graves there, labouring to exhume and identify victims with the ultimate aim of returning them to surviving family members. Incredibly, it wasn’t until 2007 - fully 50 years after the last execution in Paterna - and the socialist government of José Luis Zapatero that the rights of victims and their families were enshrined in the Ley de la Memoria Histórica (Law of Historical Memory), since expanded and extended in the teeth of right-wing opposition by the 2022 Ley de la Memoria Democrática (Law of Democratic Memory).

Work to carry out the exhumations and identifications promised in law has ebbed and flowed over the years, with right-wing governments (both local and national) reluctant to provide the requisite funds. This cavalier treatment of the sensibilities of thousands of families of Civil War victims is of a piece with Partido Popular leader Alberto Núñez Feijóo's description of the Civil War as a 'a grandads' punch-up' (una pelea entre abuelos). All the foot-dragging meant that the first successful exhumation and identification in Paterna was in 2012 when, after a four-year battle, Josefa 'Pepica' Celda was able to recover the remains of her father from mass grave number 126.

I went on a tour of the Ethnographical Museum exhibition last Sunday. Our guide was one of the forensic archaeologists tasked with recovering and identifying the remains in Paterna’s mass graves. She was visibly moved as she described the nature of her work, especially at the moment of confirming to a family member that the bones she’d recovered were indeed those of a father or grandfather - and in rarer cases a mother or grandmother.

The exhibition compares the mass executions carried out during Franco’s dictatorship with others round the world, pointing out how late and patchy the reckoning in Spain has been compared with other cases. There are memorabilia of all sorts on display: postcards sent from prison, women’s brooches, rope used to tie prisoners’ hands, and small glass bottles containing a name that kindly (or bribed) gravediggers left under the necks of victims in the hope of future identification.

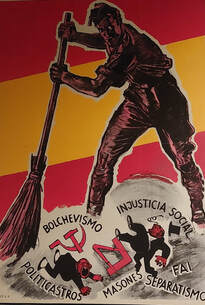

In among all these relics and reminders the guide drew our attention to a fascist propaganda poster depicting a nationalist soldier sweeping away bumbling politicians, masons, separatism, Bolshevism, anarchist militants and ‘social injustice’ - in other words the social cleansing of republican undesirables, leaving the way clear for the dictatorship of Franco’s pensamiento único, or ‘monolithic thinking’. (This is the poster at the top of the page if you're reading this on a mobile phone).

Officially 2,238 Republican sympathisers were executed, though there are likely to have been more. Across Spain there are at least 2,500 mass graves holding the bodies of about 130,000 victims of the Civil War and Franco’s subsequent dictatorship. There may be twice as many as that, some of which will have been lost forever, razed by the heavy machinery that moved into cemeteries across Spain in 1975 after Franco’s death to destroy the evidence of his brutal repression.

The Paterna cemetery was spared, which is why every Monday forensic archaeologists work on one of the 135 mass graves there, labouring to exhume and identify victims with the ultimate aim of returning them to surviving family members. Incredibly, it wasn’t until 2007 - fully 50 years after the last execution in Paterna - and the socialist government of José Luis Zapatero that the rights of victims and their families were enshrined in the Ley de la Memoria Histórica (Law of Historical Memory), since expanded and extended in the teeth of right-wing opposition by the 2022 Ley de la Memoria Democrática (Law of Democratic Memory).

Work to carry out the exhumations and identifications promised in law has ebbed and flowed over the years, with right-wing governments (both local and national) reluctant to provide the requisite funds. This cavalier treatment of the sensibilities of thousands of families of Civil War victims is of a piece with Partido Popular leader Alberto Núñez Feijóo's description of the Civil War as a 'a grandads' punch-up' (una pelea entre abuelos). All the foot-dragging meant that the first successful exhumation and identification in Paterna was in 2012 when, after a four-year battle, Josefa 'Pepica' Celda was able to recover the remains of her father from mass grave number 126.

I went on a tour of the Ethnographical Museum exhibition last Sunday. Our guide was one of the forensic archaeologists tasked with recovering and identifying the remains in Paterna’s mass graves. She was visibly moved as she described the nature of her work, especially at the moment of confirming to a family member that the bones she’d recovered were indeed those of a father or grandfather - and in rarer cases a mother or grandmother.

The exhibition compares the mass executions carried out during Franco’s dictatorship with others round the world, pointing out how late and patchy the reckoning in Spain has been compared with other cases. There are memorabilia of all sorts on display: postcards sent from prison, women’s brooches, rope used to tie prisoners’ hands, and small glass bottles containing a name that kindly (or bribed) gravediggers left under the necks of victims in the hope of future identification.

In among all these relics and reminders the guide drew our attention to a fascist propaganda poster depicting a nationalist soldier sweeping away bumbling politicians, masons, separatism, Bolshevism, anarchist militants and ‘social injustice’ - in other words the social cleansing of republican undesirables, leaving the way clear for the dictatorship of Franco’s pensamiento único, or ‘monolithic thinking’. (This is the poster at the top of the page if you're reading this on a mobile phone).

The guide asked us if the poster reminded us of anything, and a much more recent image sprang to mind. During the recent Spanish General Election campaign in June/July the extreme right-wing party Vox hung a huge banner in central Madrid employing an identical purifying trope, symbolising, in this case, the purging of what it regards as loathsome elements in contemporary Spain: feminists, ecologists, the LGTBIQ+ community, communists, Catalan separatists, and okupas (squatters).

Vox, the party that would like to rid Spain of progressives just as Franco wanted to purge the country of Republicans, is the third largest political force in the country. It won over 3 million votes in the July 2023 General Election, has 33 seats in the Cortes Generales (House of Commons equivalent), is in coalition with the right-wing Partido Popular in five of Spain’s seventeen Autonomies, and in the May local elections it trebled the number of Vox councillors in villages and towns across the country.

In Paterna there is a track locally known as the camí de la sang, or ‘the path of blood’. The track leads from the wall where enemies of the Franco regime were executed to the mass graves into which they were tossed. In fact there were two paths of blood. The first led through the town to the cemetery, and citizens complained about the crimson trail left by the trucks transporting executed prisoners from the paredón to the cemetery. So the trucks were rerouted so the citizens of Paterna wouldn’t be confronted with the grisly effects of Franco’s social cleansing. Turning a blind eye in Paterna until the killing stopped in 1956 led to institutional forgetting across Spain, but as Yōko Ogawa points out in her novel The Memory Police, 'Memories are a lot tougher than you might think, just like the hearts that hold them'. Josefa 'Pepica' Celda's heart, for example.

Leaving the Arqueología de la memoria exhibition it occurred to me that there is another path, one which takes us directly from Franco’s social cleansing poster to the buttons and brooches, the pins and postcards, the miserable memorabilia of Paterna’s mass graves. We’d do well to listen to the grim historical echo present in Vox’s Madrid banner otherwise history may repeat itself, and not as farce as Karl Marx predicted in The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, but as catastrophe.

Vox, the party that would like to rid Spain of progressives just as Franco wanted to purge the country of Republicans, is the third largest political force in the country. It won over 3 million votes in the July 2023 General Election, has 33 seats in the Cortes Generales (House of Commons equivalent), is in coalition with the right-wing Partido Popular in five of Spain’s seventeen Autonomies, and in the May local elections it trebled the number of Vox councillors in villages and towns across the country.

In Paterna there is a track locally known as the camí de la sang, or ‘the path of blood’. The track leads from the wall where enemies of the Franco regime were executed to the mass graves into which they were tossed. In fact there were two paths of blood. The first led through the town to the cemetery, and citizens complained about the crimson trail left by the trucks transporting executed prisoners from the paredón to the cemetery. So the trucks were rerouted so the citizens of Paterna wouldn’t be confronted with the grisly effects of Franco’s social cleansing. Turning a blind eye in Paterna until the killing stopped in 1956 led to institutional forgetting across Spain, but as Yōko Ogawa points out in her novel The Memory Police, 'Memories are a lot tougher than you might think, just like the hearts that hold them'. Josefa 'Pepica' Celda's heart, for example.

Leaving the Arqueología de la memoria exhibition it occurred to me that there is another path, one which takes us directly from Franco’s social cleansing poster to the buttons and brooches, the pins and postcards, the miserable memorabilia of Paterna’s mass graves. We’d do well to listen to the grim historical echo present in Vox’s Madrid banner otherwise history may repeat itself, and not as farce as Karl Marx predicted in The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, but as catastrophe.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed