3406 words: 10-minute read

A few weeks ago I went on a walking tour of València, taking in the landmarks of Joaquín Sorolla’s life in the city. This year is the 100th anniversary of the death of the 'painter of light' so there have been plenty of tours to choose from. The blurb that accompanied a major exhibition of his work at the National Gallery in London in 2019 made two accurate observations. The first was that ‘Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida (1863–1923) is probably a name few know in the UK’, and the second, ‘in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, he was among the most famous of living artists in Europe’. Quite what has happened to turn him from a star in 1909, the date of the last major exhibition devoted to his work, in the Grafton Galleries in London, to an also-ran in the 2020s is hard to say. There is only one Sorolla painting on display in the National Gallery, The Drunkard, acquired as recently as 2020 with a £325,000 legacy left by the architect David Med.

The Guardian’s art critic, Laura Cumming, left the 2019 exhibition with the impression that his work is flashy rather than substantial, though she grudgingly concedes that, ‘It is hardly possible to stand before these enormous canvases, thick with paint, without feeling at least something of their appeal’. There may be some ignorance at work here, for Cumming berates Sorolla for ‘verging on plagiarism’, citing early copies of the work of Velázquez and Goya without knowing, apparently, that these were a condition of the continuation of the prestigious grant that took him to Italy and that Sorolla produced only with the greatest reluctance. Sorolla remains hugely popular in his native Spain and over 160,000 people visited the 2019 exhibition at the National Gallery. Perhaps the thousands of New Yorkers who queued in the snow to see his work in 1909 weren’t so wrong after all. A case of you can’t like what you don’t see?

He is best-known for his luminous depictions of the Cabanyal fisherfolk on València’s Malvarrosa beach at the turn of the 20th century. Just up from the beach where he used to paint they’re restoring the Casa de Bous which housed the animals that dragged the fishing boats out of the water at the end of a day’s faena. Rumour has it that Sorolla used to store his canvasses and paints in the Casa de Bous, or at least in a small studio nearby. Back then the Casa was right on the beach but now it’s about 200 metres away, land that has been reclaimed and is now occupied by sunseekers for whom the beach and sea are a source of entertainment rather than endeavour.

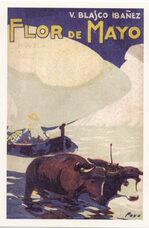

On the walking tour we passed down the Carrer de las Mantas where Sorolla was born, close to the fabric shop his parents ran. Above the door is a plaque commemorating his birth, and the bottom half of the plaque is a version of a recurring image in his paintings: bulls pulling boats out of the sea up the Malvarrosa beach. As we sought shade from the sun pouring into the street the guide showed us the cover a book on her iPad. It was the cover of an old edition of a novel, Flor de Mayo, by one of València´s other favourite sons, Vicente Blasco Ibáñez. The cover was itself a version of Sorolla´s bulls on the beach, and given these various coincidences and because I hadn´t read Flor de Mayo, I decided to go and look for a copy.

The tour ended quite near the Mercat Central, a masterpiece of Valencian Art Nouveau and a magnet for the increasing number of tourists to the city, happy to pay inflated prices for the goods on offer - or oblivious to the fact that they’re doing so. The hen parties and stag dos will be unaware that they are within throwing up distance of the spot where Margarida (Miquel) Borràs was executed in 1460 for the crime of dressing as a woman, private parts on display for all to see as s/he swung from the hangman’s noose.

I knew there were a number of second-hand bookshops in the area and I located one on Google Maps, just a couple of hundred metres from where I was standing - Auca Llibres Antics. Even though there was neither air conditioning nor a simple fan in the shop it was still a relief to take refuge from the sun. The shop was filled with that ineffable aroma of old books, the accumulated odour of decades - even centuries - of the attempts by men and women to instruct, cajole, and entertain their readers.

The owner was at the back of the shop and I asked him if he had a copy of Flor de Mayo. He scanned the top shelf of a bookcase full of novels, essays and short stories by Blasco Ibáñez and shook his head. Then he told me to wait, maybe he’d have a copy round the back, he said. I waited a few minutes, taking down a book called Razón mecánica y razón dialéctica by Enrique Tierno Galván, mayor of Madrid from 1979 to 1986, ruminating on the contrast between him and the current president of the Comunidad de Madrid, Isabel Díaz Ayuso, best known for claiming that climate change is a communist plot most effectively dealt with by a plant pot on our balconies and that one of the great things about Madrid is that it’s big enough for you not to bump into your ex.

The shop owner returned with a smile on his face - holding a copy of Flor de Mayo. And astonishingly it wasn’t just any old copy but the very edition the tour guide had shown us on her iPad, complete with Sorolla’s arresting depiction of bulls pulling boats out of the sea on to the Malvarrosa beach. Expecting the 100 year-old book to be well outside my price range I tentatively asked the shop owner how much he wanted for it. Five euros he said. I thought I’d misheard so I asked again. Five euros, he repeated. He said the spine was held together by sellotape (it was) so he really couldn’t charge me any more, and besides, he was retiring at the end of the year so he had to either sell or give away all the books in the shop by then. I looked at the magnificent accumulation around me, mentally compiling a list of people I’d tell about the treasure trove I’d just discovered. Didn’t he have anyone lined up to take over the shop, I asked him? No-one, he said. So what was going to happen to it? He shrugged his shoulders and said it would be probably be bought up and ‘repurposed’.

The Flor de Mayo edition I had bought opens with a charming 1925 ‘To the reader’ foreword by Blasco Ibáñez in which he tells us that this is his second novel (1895) after Arroz y Tartana, and that he wrote it in instalments in the republican newspaper El Pueblo which he founded. His third novel, Entre Naranjos, was published in the same way - a triumvirate of books that by turns paint pictures of Valencian life on the sea, in the city and in the countryside every bit as vivid as Sorolla’s canvases. His late 20s, recently married and with a small but growing family to maintain, were years of penury and privation - in colossal contrast to the riches of later life when royalties from novels, film scripts and copyrights poured in.

By the time of his death in 1928 he was world-famous, and Greta Garbo had taken her first starring role in Torrent (1926), based on his Entre Naranjos novel. Like Sorolla, outside of Spain Blasco Ibáñez's star in the English-speaking world has waned spectacularly since then. Again like Sorolla you can’t like what you don’t see. During my time in Spain I’ve been struck by how much more cosmopolitan Spanish reading tastes are compared to the insular British. Virtually every bookshop has a ‘translated from English’ section where both classics and contemporary fiction are readily available. There’s no equivalent in bookshops in the UK. They can read Eliot, Austen and Dickens but we can’t read Pérez Galdos, Pardo Bazán or Blasco Ibañez.

Blasco’s republicanism landed him in jail for several months in 1896 and he never wavered in his support for progressive causes. In the ‘To the reader’ foreword he recalls another Flor de Mayo memory. As it was a tale of the sea he was wont to wander the beach thinking through the plot, and occasionally he would come across a young painter working in the heat of the midday sun, ‘magically reproducing the golden light of the Mediterranean’ on his canvases. ‘We worked together,’ Blasco Ibáñez writes, ‘him on his canvasses and me on my novel. We were as brothers, until death recently pulled us apart. It was Joaquín Sorolla’.

When I first arrived in València the Plaça del Mercat was - as for any other neophyte visitor to the city - an obligatory stopping-off point. There’s not only the Mercat itself but also the 15th century civil Gothic Llotja de la Seda, trading hall and financial centre during Valencia’s medieval golden years, and the 17th century Baroque Church of Santos Juanes, atopped by an eagle-shaped weather vane which, legend has it, poor peasants would make their children look at while they crept away, leaving them to be picked up for domestic labour in bourgeois households. Just across the way from these jewels in Valencia’s medieval crown there is another shop that has been ‘repurposed’ - a chemist’s shop.

I’d first come across the shop, the Farmacia Rubió, tucked away in the Calle San Fernando just off the Plaça del Mercat, when I arrived in València about three years ago. Like many Mediterranean countries Spain boasts a host of glorious farmacias, most of them founded around the the turn of the 20th century, and the Farmacia Rubió was a startling example of the genre. The ceiling of the farmacia, founded in 1921 just as the Mercat Central itself across the Plaça was taking shape, comprised a carved wooden cupola topped off by an angel holding a pharmacopoea (book of directions for the identification of compound medicines), while the shop’s shelves, also exquisitely carved, contained the flasks and bottles that held the medicines once sold across the 100-year-old wooden counter. The floor was Valencian tiling, quite possibly sourced from nearby Manises or Meliana, preserving the ghostly footprints of the thousands of Valencians who had passed through this pharmaceutical-architectural time capsule seeking relief from affliction.

Some months after this discovery, taking a visitor round València, I went looking for the Farmacia Rubió but it had disappeared. Maybe I’d got the address wrong? Old Valencia is rather a maze and I’d got lost more than once before. But no, I was in the Calle San Fernando and the Farmacia Rubió was nowhere to be seen. Then it dawned on me. I was looking exactly where the chemist’s had been, but now it was a bicycle hire shop. The 1920s lettering outside the shop announcing what it had been? Gone. The tiling on the floor? Gone. The wooden shelves, counter and old flasks and bottles? Gone. The cupola-pharmacopoea? Still there, gazing down at the bikes, e-bikes and scooters for rent, starting at 8 euros a day.

València is very flat and it has one the best cycling infrastructures in Spain - third best after Vitoria and Sevilla. I don’t have a car and getting from A to B by bike is a safe, trouble-free and enjoyable experience. (And no, contrary to the 15-minute city conspiracists I don’t need a passport to leave the barrio). València is also experiencing a tourist boom, enjoying (as most people put it) a 9.1% increase this year compared to pre-pandemic 2019. These tourists need bikes to ride up and down the old river Turia, now converted into a 10-kilometre long park, and to get to the beach, which is why the number of bike hire shops in the city centre has exploded in recent years. It’s definitely easier to hire a bike in the middle of València than buy a packet of paracetamol.

Tourism has long been a contributor to Spain’s economy, accounting for about 13% of the country’s pre-Covid GDP. It took a huge hit during the pandemic, but the juggernaut is back up and running and any opportunity there might have been to rebalance the economy has well and truly evaporated. The new normal is very much like the old one. Scarcely believably, Francisco Franco was already testing out tourism’s promise while the Civil War was still raging. The National Spanish State Tourist Board was established in 1938, offering a nine-day tour taking in San Sebastián, Bilbao, Santander, Gijón and Oviedo, costing £8 for three meals a day and accommodation in first-class hotels. As the Fascists occupied more and more territory, routes round Andalucía, Aragón and Madrid were added, and between 1939 and 1945 some 6,000 to 20,000 tourists from Britain, Italy, Portugal, France, Germany and Australia were treated to what were effectively subsidised propaganda exercises.

The ‘touristification’ of the Spanish economy went up a gear in the early 1960s when swarms of Northern Europeans (mostly) contributed to the whitewashing of Franco’s dictatorship by flocking to the beaches of Mediterranean Spain, attracted by the ‘Spain is different’ slogan, and accompanying sun, sea and sangría. For family reasons I had occasion to spend three days at the end of August in one of Spain’s mass tourism hotspots - Benidorm. Aerial photographs of the town from the 1950s show the old town on the promontory, with orange groves sweeping down to a deserted Platja de Llevant. Now, the view from the E7 Autopista de la Mediterrànea looking down on modern Benidorm is spectacular in a different kind of way: the orange trees have gone, replaced by a forest of skyscrapers - a tribute to the architectural and logisitical ingenuity that enables almost 2 million overnight stays each year. That’s about 5,500 years of sunning, swimming, drinking, gambling and whatever else every summer, all in about 10 km² of Mediterranean coastline.

Google maps will tell you that the orange groves are now hotels, bars, restaurants, grill houses, casinos and massage parlours. Together with Trip Advisor they will also help you find somewhere to eat, but as with everything on the web you only get out what’s put in, and there’s no filter for taste. So when Fernando’s tapas bar comes up with 4.5* and you think that´ll probably be OK, be prepared for pizza out of a packet and calamari rings heated up in a microwave. It’s the sort of thing British tourists refer to as ‘cheap and cheerful’, though all it did for me was to confirm my previously uninformed prejudice that if there was a ‘p’ in Benidorm it would stand for punishment rather than pleasure.

Quite how long this tourism model can hold up is anyone’s guess, what with climate change rendering unbearable ever bigger chunks of a 24-hour day. The concept of noches tropicales (‘tropical nights’ when the temperature doesn’t go below 20°C) has been common in Spain for years. In recent years noches tórridas (25°C) have come into play, and now we’re confronted with noches infernales (‘nights from hell’) when the night time minimum is a stifling 30°C. The number of noches tórridas has doubled since 1980 and by the beginnning of August this year Melilla, Jaén and Almería had all experienced noches infernales. For the moment northern Europeans continue to flock to the Mediterranean while the Spanish are increasingly heading in the other direction, but there may come a time when scrambling for the last sun bed before heading for an overfull and overpriced restaurant staffed by men and women on minimum wages will seem a suboptimal way of spending your two weeks’ holiday a year.

A different kind of tourism, sanguinely described as turismo de calidad (‘quality tourism’), is leaving an irrevocable mark on València and other cities in Spain like it. The old city has been falling apart for decades and there isn’t enough public money to put it back together again. Private investors who have crumbling buildings restored want a return on their money, and the quickest and most assured benefits are not through building affordable housing but by providing tourist apartments. They’re readily identifiable in València’s old city - every tourist apartment balcony has two IKEA chairs and a little table. In some barrios you see nothing else. The result is a hollowed-out city centre, where the shops that used to cater for the people who lived and worked there have been replaced by restaurants, bijou bars, souvenir shops - and bike rentals. Tourists in València don’t need flour or eggs, but they do need a bike.

All this has put the recently-elected right-wing government in València in something of a quandary because cycle lanes play a big part in the culture wars they’ve drummed up in recent months. They’re particularly hated by Vox, the extreme right party with which the Partido Popular entered into coalition in towns, cities and autonomies across Spain after this year’s May local elections. One Vox candidate posed next to a cycle lane in the the town of Elche in the province of Alicante, holding a pneumatic drill. Sure enough, the lane has been removed, ostensibly because parents of a semi-private school in the street couldn’t stop to pick up their children. The measure could turn out to be expensive. In many cases these lanes have been part-funded by the European Union, and the mayor of Logroño is faced with returning 6.5 million euros to the EU if he carries out his election promise of removing the town’s main east-west cycle lane.

In València the right-wing coalition is carrying out a cycle lane survey, with six under threat under the guise of ‘improved safety’. One has already been removed, apparently after citizen representation. One wonders who these citizens are, given that the cycle lane was put in after local citizens demanded it in the last round of participatory budgeting (initiated by the previous left-wing administration). At the same time the coalition has a plan to incentivise tourism, and is committed to abolishing the tourist tax that was due to come into effect in December. Incentivise tourism? Someone needs to show them the Instagram and TikTok accounts of swarms of Northern Europeans on their hire bikes criss-crossing the city in the lanes created by the left-wing government narrowly voted out of power in May.

València will be Europe's Green Capital in 2024, an accolade which 'recognizes the city's efforts to improve the environment and the quality of life of its residents and visitors alike. It takes into account factors such as the numerous green spaces and sustainable mobility initiatives that can be enjoyed in the city'. The measures that led to this award are being dismantled by the Partido Popular and by Vox, with the former systematically subverting sustainable mobility initiatives, and the latter consistently voting against measures to deal with anthropogenic climate change. Perhaps the European Commission should have a rethink.

The other day I went back to Auca Llibres Antics, a couple of months closer now to final closure. It’s still hot in there even in September, and the heady smell of old books seems even stronger than when I first went in, as if they’ve been marinating all summer. Everything is now being sold at a 50% discount, and I bought a copy of Arturo Barea’s La Raíz Rota. Barea is best known for his autobiographical trilogy La Forja de un Rebelde, first published in English in three volumes as The Forging of a Rebel between 1941 and 1946. (There is an excellent account of Barea's remarkable life by William Chislett here). Barea's extraordinary testament covers his early life in Madrid where his mother made her living washing clothes in the Manzanares river, through to his military service and participation in the Rif War in the Spanish Protectorate of Morocco, and finally to his role on the Republican side in the Spanish Civil War. The Fascist victory forced Barea into exile, first in France and then England where he spent the rest of his life, before dying in Faringdon, Oxfordshire in 1957. He wrote La Forja in Spanish and it was translated into English by his second wife Ilsa Pollak. The first Spanish edition wasn’t published until 1951 and the first publication in Spain itself was in 1978, three years after Franco’s death. In La Raíz Rota, the book I bought, Barea imagines a life denied to him: the fictional protagonist Antolín Moreno returns in 1949 to post-Civil War Spain, in the grip of a dictatorship the extent of whose ferocity and cruelty is only now becoming clear, even to those who lived through it.

The copy of La Raíz Rota with which I walked out of Auca Llibres Antics was published in Buenos Aires in 1955. Its simple cover is protected by a cellophane wrapper, the paper is thick, the stitching is simple and the page edges are roughly cut. It smells … well, it smells like an old book.

It cost me 12.50 euros, a day-and-a-half’s bike hire.

Andrew Dobson

València

September 2023

A few weeks ago I went on a walking tour of València, taking in the landmarks of Joaquín Sorolla’s life in the city. This year is the 100th anniversary of the death of the 'painter of light' so there have been plenty of tours to choose from. The blurb that accompanied a major exhibition of his work at the National Gallery in London in 2019 made two accurate observations. The first was that ‘Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida (1863–1923) is probably a name few know in the UK’, and the second, ‘in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, he was among the most famous of living artists in Europe’. Quite what has happened to turn him from a star in 1909, the date of the last major exhibition devoted to his work, in the Grafton Galleries in London, to an also-ran in the 2020s is hard to say. There is only one Sorolla painting on display in the National Gallery, The Drunkard, acquired as recently as 2020 with a £325,000 legacy left by the architect David Med.

The Guardian’s art critic, Laura Cumming, left the 2019 exhibition with the impression that his work is flashy rather than substantial, though she grudgingly concedes that, ‘It is hardly possible to stand before these enormous canvases, thick with paint, without feeling at least something of their appeal’. There may be some ignorance at work here, for Cumming berates Sorolla for ‘verging on plagiarism’, citing early copies of the work of Velázquez and Goya without knowing, apparently, that these were a condition of the continuation of the prestigious grant that took him to Italy and that Sorolla produced only with the greatest reluctance. Sorolla remains hugely popular in his native Spain and over 160,000 people visited the 2019 exhibition at the National Gallery. Perhaps the thousands of New Yorkers who queued in the snow to see his work in 1909 weren’t so wrong after all. A case of you can’t like what you don’t see?

He is best-known for his luminous depictions of the Cabanyal fisherfolk on València’s Malvarrosa beach at the turn of the 20th century. Just up from the beach where he used to paint they’re restoring the Casa de Bous which housed the animals that dragged the fishing boats out of the water at the end of a day’s faena. Rumour has it that Sorolla used to store his canvasses and paints in the Casa de Bous, or at least in a small studio nearby. Back then the Casa was right on the beach but now it’s about 200 metres away, land that has been reclaimed and is now occupied by sunseekers for whom the beach and sea are a source of entertainment rather than endeavour.

On the walking tour we passed down the Carrer de las Mantas where Sorolla was born, close to the fabric shop his parents ran. Above the door is a plaque commemorating his birth, and the bottom half of the plaque is a version of a recurring image in his paintings: bulls pulling boats out of the sea up the Malvarrosa beach. As we sought shade from the sun pouring into the street the guide showed us the cover a book on her iPad. It was the cover of an old edition of a novel, Flor de Mayo, by one of València´s other favourite sons, Vicente Blasco Ibáñez. The cover was itself a version of Sorolla´s bulls on the beach, and given these various coincidences and because I hadn´t read Flor de Mayo, I decided to go and look for a copy.

The tour ended quite near the Mercat Central, a masterpiece of Valencian Art Nouveau and a magnet for the increasing number of tourists to the city, happy to pay inflated prices for the goods on offer - or oblivious to the fact that they’re doing so. The hen parties and stag dos will be unaware that they are within throwing up distance of the spot where Margarida (Miquel) Borràs was executed in 1460 for the crime of dressing as a woman, private parts on display for all to see as s/he swung from the hangman’s noose.

I knew there were a number of second-hand bookshops in the area and I located one on Google Maps, just a couple of hundred metres from where I was standing - Auca Llibres Antics. Even though there was neither air conditioning nor a simple fan in the shop it was still a relief to take refuge from the sun. The shop was filled with that ineffable aroma of old books, the accumulated odour of decades - even centuries - of the attempts by men and women to instruct, cajole, and entertain their readers.

The owner was at the back of the shop and I asked him if he had a copy of Flor de Mayo. He scanned the top shelf of a bookcase full of novels, essays and short stories by Blasco Ibáñez and shook his head. Then he told me to wait, maybe he’d have a copy round the back, he said. I waited a few minutes, taking down a book called Razón mecánica y razón dialéctica by Enrique Tierno Galván, mayor of Madrid from 1979 to 1986, ruminating on the contrast between him and the current president of the Comunidad de Madrid, Isabel Díaz Ayuso, best known for claiming that climate change is a communist plot most effectively dealt with by a plant pot on our balconies and that one of the great things about Madrid is that it’s big enough for you not to bump into your ex.

The shop owner returned with a smile on his face - holding a copy of Flor de Mayo. And astonishingly it wasn’t just any old copy but the very edition the tour guide had shown us on her iPad, complete with Sorolla’s arresting depiction of bulls pulling boats out of the sea on to the Malvarrosa beach. Expecting the 100 year-old book to be well outside my price range I tentatively asked the shop owner how much he wanted for it. Five euros he said. I thought I’d misheard so I asked again. Five euros, he repeated. He said the spine was held together by sellotape (it was) so he really couldn’t charge me any more, and besides, he was retiring at the end of the year so he had to either sell or give away all the books in the shop by then. I looked at the magnificent accumulation around me, mentally compiling a list of people I’d tell about the treasure trove I’d just discovered. Didn’t he have anyone lined up to take over the shop, I asked him? No-one, he said. So what was going to happen to it? He shrugged his shoulders and said it would be probably be bought up and ‘repurposed’.

The Flor de Mayo edition I had bought opens with a charming 1925 ‘To the reader’ foreword by Blasco Ibáñez in which he tells us that this is his second novel (1895) after Arroz y Tartana, and that he wrote it in instalments in the republican newspaper El Pueblo which he founded. His third novel, Entre Naranjos, was published in the same way - a triumvirate of books that by turns paint pictures of Valencian life on the sea, in the city and in the countryside every bit as vivid as Sorolla’s canvases. His late 20s, recently married and with a small but growing family to maintain, were years of penury and privation - in colossal contrast to the riches of later life when royalties from novels, film scripts and copyrights poured in.

By the time of his death in 1928 he was world-famous, and Greta Garbo had taken her first starring role in Torrent (1926), based on his Entre Naranjos novel. Like Sorolla, outside of Spain Blasco Ibáñez's star in the English-speaking world has waned spectacularly since then. Again like Sorolla you can’t like what you don’t see. During my time in Spain I’ve been struck by how much more cosmopolitan Spanish reading tastes are compared to the insular British. Virtually every bookshop has a ‘translated from English’ section where both classics and contemporary fiction are readily available. There’s no equivalent in bookshops in the UK. They can read Eliot, Austen and Dickens but we can’t read Pérez Galdos, Pardo Bazán or Blasco Ibañez.

Blasco’s republicanism landed him in jail for several months in 1896 and he never wavered in his support for progressive causes. In the ‘To the reader’ foreword he recalls another Flor de Mayo memory. As it was a tale of the sea he was wont to wander the beach thinking through the plot, and occasionally he would come across a young painter working in the heat of the midday sun, ‘magically reproducing the golden light of the Mediterranean’ on his canvases. ‘We worked together,’ Blasco Ibáñez writes, ‘him on his canvasses and me on my novel. We were as brothers, until death recently pulled us apart. It was Joaquín Sorolla’.

When I first arrived in València the Plaça del Mercat was - as for any other neophyte visitor to the city - an obligatory stopping-off point. There’s not only the Mercat itself but also the 15th century civil Gothic Llotja de la Seda, trading hall and financial centre during Valencia’s medieval golden years, and the 17th century Baroque Church of Santos Juanes, atopped by an eagle-shaped weather vane which, legend has it, poor peasants would make their children look at while they crept away, leaving them to be picked up for domestic labour in bourgeois households. Just across the way from these jewels in Valencia’s medieval crown there is another shop that has been ‘repurposed’ - a chemist’s shop.

I’d first come across the shop, the Farmacia Rubió, tucked away in the Calle San Fernando just off the Plaça del Mercat, when I arrived in València about three years ago. Like many Mediterranean countries Spain boasts a host of glorious farmacias, most of them founded around the the turn of the 20th century, and the Farmacia Rubió was a startling example of the genre. The ceiling of the farmacia, founded in 1921 just as the Mercat Central itself across the Plaça was taking shape, comprised a carved wooden cupola topped off by an angel holding a pharmacopoea (book of directions for the identification of compound medicines), while the shop’s shelves, also exquisitely carved, contained the flasks and bottles that held the medicines once sold across the 100-year-old wooden counter. The floor was Valencian tiling, quite possibly sourced from nearby Manises or Meliana, preserving the ghostly footprints of the thousands of Valencians who had passed through this pharmaceutical-architectural time capsule seeking relief from affliction.

Some months after this discovery, taking a visitor round València, I went looking for the Farmacia Rubió but it had disappeared. Maybe I’d got the address wrong? Old Valencia is rather a maze and I’d got lost more than once before. But no, I was in the Calle San Fernando and the Farmacia Rubió was nowhere to be seen. Then it dawned on me. I was looking exactly where the chemist’s had been, but now it was a bicycle hire shop. The 1920s lettering outside the shop announcing what it had been? Gone. The tiling on the floor? Gone. The wooden shelves, counter and old flasks and bottles? Gone. The cupola-pharmacopoea? Still there, gazing down at the bikes, e-bikes and scooters for rent, starting at 8 euros a day.

València is very flat and it has one the best cycling infrastructures in Spain - third best after Vitoria and Sevilla. I don’t have a car and getting from A to B by bike is a safe, trouble-free and enjoyable experience. (And no, contrary to the 15-minute city conspiracists I don’t need a passport to leave the barrio). València is also experiencing a tourist boom, enjoying (as most people put it) a 9.1% increase this year compared to pre-pandemic 2019. These tourists need bikes to ride up and down the old river Turia, now converted into a 10-kilometre long park, and to get to the beach, which is why the number of bike hire shops in the city centre has exploded in recent years. It’s definitely easier to hire a bike in the middle of València than buy a packet of paracetamol.

Tourism has long been a contributor to Spain’s economy, accounting for about 13% of the country’s pre-Covid GDP. It took a huge hit during the pandemic, but the juggernaut is back up and running and any opportunity there might have been to rebalance the economy has well and truly evaporated. The new normal is very much like the old one. Scarcely believably, Francisco Franco was already testing out tourism’s promise while the Civil War was still raging. The National Spanish State Tourist Board was established in 1938, offering a nine-day tour taking in San Sebastián, Bilbao, Santander, Gijón and Oviedo, costing £8 for three meals a day and accommodation in first-class hotels. As the Fascists occupied more and more territory, routes round Andalucía, Aragón and Madrid were added, and between 1939 and 1945 some 6,000 to 20,000 tourists from Britain, Italy, Portugal, France, Germany and Australia were treated to what were effectively subsidised propaganda exercises.

The ‘touristification’ of the Spanish economy went up a gear in the early 1960s when swarms of Northern Europeans (mostly) contributed to the whitewashing of Franco’s dictatorship by flocking to the beaches of Mediterranean Spain, attracted by the ‘Spain is different’ slogan, and accompanying sun, sea and sangría. For family reasons I had occasion to spend three days at the end of August in one of Spain’s mass tourism hotspots - Benidorm. Aerial photographs of the town from the 1950s show the old town on the promontory, with orange groves sweeping down to a deserted Platja de Llevant. Now, the view from the E7 Autopista de la Mediterrànea looking down on modern Benidorm is spectacular in a different kind of way: the orange trees have gone, replaced by a forest of skyscrapers - a tribute to the architectural and logisitical ingenuity that enables almost 2 million overnight stays each year. That’s about 5,500 years of sunning, swimming, drinking, gambling and whatever else every summer, all in about 10 km² of Mediterranean coastline.

Google maps will tell you that the orange groves are now hotels, bars, restaurants, grill houses, casinos and massage parlours. Together with Trip Advisor they will also help you find somewhere to eat, but as with everything on the web you only get out what’s put in, and there’s no filter for taste. So when Fernando’s tapas bar comes up with 4.5* and you think that´ll probably be OK, be prepared for pizza out of a packet and calamari rings heated up in a microwave. It’s the sort of thing British tourists refer to as ‘cheap and cheerful’, though all it did for me was to confirm my previously uninformed prejudice that if there was a ‘p’ in Benidorm it would stand for punishment rather than pleasure.

Quite how long this tourism model can hold up is anyone’s guess, what with climate change rendering unbearable ever bigger chunks of a 24-hour day. The concept of noches tropicales (‘tropical nights’ when the temperature doesn’t go below 20°C) has been common in Spain for years. In recent years noches tórridas (25°C) have come into play, and now we’re confronted with noches infernales (‘nights from hell’) when the night time minimum is a stifling 30°C. The number of noches tórridas has doubled since 1980 and by the beginnning of August this year Melilla, Jaén and Almería had all experienced noches infernales. For the moment northern Europeans continue to flock to the Mediterranean while the Spanish are increasingly heading in the other direction, but there may come a time when scrambling for the last sun bed before heading for an overfull and overpriced restaurant staffed by men and women on minimum wages will seem a suboptimal way of spending your two weeks’ holiday a year.

A different kind of tourism, sanguinely described as turismo de calidad (‘quality tourism’), is leaving an irrevocable mark on València and other cities in Spain like it. The old city has been falling apart for decades and there isn’t enough public money to put it back together again. Private investors who have crumbling buildings restored want a return on their money, and the quickest and most assured benefits are not through building affordable housing but by providing tourist apartments. They’re readily identifiable in València’s old city - every tourist apartment balcony has two IKEA chairs and a little table. In some barrios you see nothing else. The result is a hollowed-out city centre, where the shops that used to cater for the people who lived and worked there have been replaced by restaurants, bijou bars, souvenir shops - and bike rentals. Tourists in València don’t need flour or eggs, but they do need a bike.

All this has put the recently-elected right-wing government in València in something of a quandary because cycle lanes play a big part in the culture wars they’ve drummed up in recent months. They’re particularly hated by Vox, the extreme right party with which the Partido Popular entered into coalition in towns, cities and autonomies across Spain after this year’s May local elections. One Vox candidate posed next to a cycle lane in the the town of Elche in the province of Alicante, holding a pneumatic drill. Sure enough, the lane has been removed, ostensibly because parents of a semi-private school in the street couldn’t stop to pick up their children. The measure could turn out to be expensive. In many cases these lanes have been part-funded by the European Union, and the mayor of Logroño is faced with returning 6.5 million euros to the EU if he carries out his election promise of removing the town’s main east-west cycle lane.

In València the right-wing coalition is carrying out a cycle lane survey, with six under threat under the guise of ‘improved safety’. One has already been removed, apparently after citizen representation. One wonders who these citizens are, given that the cycle lane was put in after local citizens demanded it in the last round of participatory budgeting (initiated by the previous left-wing administration). At the same time the coalition has a plan to incentivise tourism, and is committed to abolishing the tourist tax that was due to come into effect in December. Incentivise tourism? Someone needs to show them the Instagram and TikTok accounts of swarms of Northern Europeans on their hire bikes criss-crossing the city in the lanes created by the left-wing government narrowly voted out of power in May.

València will be Europe's Green Capital in 2024, an accolade which 'recognizes the city's efforts to improve the environment and the quality of life of its residents and visitors alike. It takes into account factors such as the numerous green spaces and sustainable mobility initiatives that can be enjoyed in the city'. The measures that led to this award are being dismantled by the Partido Popular and by Vox, with the former systematically subverting sustainable mobility initiatives, and the latter consistently voting against measures to deal with anthropogenic climate change. Perhaps the European Commission should have a rethink.

The other day I went back to Auca Llibres Antics, a couple of months closer now to final closure. It’s still hot in there even in September, and the heady smell of old books seems even stronger than when I first went in, as if they’ve been marinating all summer. Everything is now being sold at a 50% discount, and I bought a copy of Arturo Barea’s La Raíz Rota. Barea is best known for his autobiographical trilogy La Forja de un Rebelde, first published in English in three volumes as The Forging of a Rebel between 1941 and 1946. (There is an excellent account of Barea's remarkable life by William Chislett here). Barea's extraordinary testament covers his early life in Madrid where his mother made her living washing clothes in the Manzanares river, through to his military service and participation in the Rif War in the Spanish Protectorate of Morocco, and finally to his role on the Republican side in the Spanish Civil War. The Fascist victory forced Barea into exile, first in France and then England where he spent the rest of his life, before dying in Faringdon, Oxfordshire in 1957. He wrote La Forja in Spanish and it was translated into English by his second wife Ilsa Pollak. The first Spanish edition wasn’t published until 1951 and the first publication in Spain itself was in 1978, three years after Franco’s death. In La Raíz Rota, the book I bought, Barea imagines a life denied to him: the fictional protagonist Antolín Moreno returns in 1949 to post-Civil War Spain, in the grip of a dictatorship the extent of whose ferocity and cruelty is only now becoming clear, even to those who lived through it.

The copy of La Raíz Rota with which I walked out of Auca Llibres Antics was published in Buenos Aires in 1955. Its simple cover is protected by a cellophane wrapper, the paper is thick, the stitching is simple and the page edges are roughly cut. It smells … well, it smells like an old book.

It cost me 12.50 euros, a day-and-a-half’s bike hire.

Andrew Dobson

València

September 2023

RSS Feed

RSS Feed