Naomi Klein has the knack of distilling big themes in striking book titles - No Logo, The Shock Doctrine - and for me at least every new Klein book is an 'event'. Her most recent one, Doppelganger, more than lives up to expectations, dealing as it does with the enormous topic of how the themes of left-wing progressive politics have been taken up so successfully by the populist right (at least that's my reading of the book's principal theme). The whole book is prompted by Klein's experience of an increasing confusion between her and what she calls 'Other Naomi', Naomi Wolf, probably best known for her 'Beauty Myth' book.

There was a time when the confusion might have been just a mild irritation, and politically unimportant in that in her Beauty Myth phase Naomi Wolf was widely regarded (rightly or wrongly) as a progressive feminist - like Naomi Klein. But the alarm bells began to ring when, as Klein puts it, 'Covid changed everything'. (And it did, in ways which the left has largely failed to come to terms with). Wolf began to be associated with COVID denialism, and the anti-lockdown and anti-vaccination movements - the last of which she linked (along with plenty of others) with conspiracy theories around elite control of the global population. At this point the two Naomis confusion became very troubling for Klein as people began to wonder what on earth had happened to her.

The question is: what had happened to Naomi Wolf? Her search for an answer led Klein down the rabbit hole in which the internet attention economy was working at full throttle - to Wolf's benefit. And the wilder the conspiracy theory the greater the attention. Thankfully, though, Klein doesn't put all this down to some personality problem in Wolf, or to her putative desire to maximise the monetisation of attention. She - rightly I think - signals the failure of the left to deal with the issues that preoccupy so many today, and that have been picked up by the right in its own grotesque fashion. These are: overweening state power (especially in the guise of surveillance), individual freedom, and security.

As Klein puts it: 'Issues we had once championed had gone dormant in a great many spaces'. She commends Wolf's sense of strategy and writes, 'it's highly strategic to pick up the resonant issues that your opponents have left carelessly unattended'. Had we been 'too timid and obedient during the COVID era?' she asks, too ready to accept 'pandemic measures that offloaded so much onto individuals'.

Klein sketches the alternative road, conspicuously not followed by the left as it wholeheartedly went along with the measures mandated by governments' emergency measures around the world. What happened to the 'bigger-ticket investments in strengthening public schools, hospitals and transit systems' she asks? Of course these measures couldn't have been put in place overnight, which is why we must lay the blame for the current success of right-wing populism at the feet of the left which has so failed - over the last two decades at least - to put in the place the measures that would have undergirded a less prophylactic approach to the COVID pandemic.

(It's tempting to wonder how different things would have been, in the UK at least, had Brexit not got in the way of Jeremy Corbyn winning the 2019 election).

So, having articulated a response that focuses upstream on structure deficits rather than downstream on individual 'responsibility', it's disappointing to see Klein resort to a resetting of individual psychology as the solution to all this. In this vein she appeals to 'unselfing' as the route to a better, kinder world, in which we aim not to 'maximise the advantage in our lives ... but to maximise all of life'.

The positive aspect of this, for me at least, is the appeal to a universalist vocabulary that the left has largely abandoned in favour of a fissiparous identity politics that favours solipsism over solidarity, leading, as Klein puts it, to a 'splintering into smaller and smaller groups'. 'Splintering', she rightly says, 'is tantamount to surrender'. She acknowledges that, 'race, gender, sexual orientation, class and nationality shape our distinct needs, experiences, and historical debts', but avers that we must 'build on a *shared* interest in challenging concentrated power and wealth' (my emphasis). Amen to that, but I'm not sure that 'unselfing' has sufficient heft to unravel the oligarchic powers with which we're confronted.

In this sense, Doppelganger ends not with a bang but a whimper - a sign, perhaps of the magnitude of the task confronting those on the left seeking to stem the right-wing populist tide. We won't manage this by name-calling, by being patronising, or by underestimating the concerns that propel this tide.

Because governments are indeed increasing surveillance, elites have indeed made obscene amounts of money out of masks and vaccinations, and people really do feel increasingly insecure as the welfare state is hollowed out by swivel-eyed small-state libertarians. Back in the day people would have turned to the left for solutions to these problems, but in the mirror world described by Klein it's those very same small-state libertarians who claim to hold the key to salvation. And people - too many people - believe them.

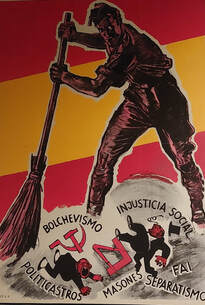

These are very real concerns and the left's failure to address them has left the field wide open to the right that presents itself as anti-system. Only in the Doppelganger world described by Klein can elites intent on securing the system and extending its influence present themselves as tearing it down, in favour - they say - of the class with precisely the most to lose from 'Making America (or Argentina, or Hungary, or the UK, or Spain or ...) Great Again'.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed